Turn of the times – Harxheim from 1933 to 1945

National Socialist ideas fell on fertile ground in Rheinhessen and Harxheim was no exception. Soon after the seizure of power in 1933, National Socialist structures were also established in our town. Opponents of the system were subjected to hostility and reprisals. Harxheim, like many places in Rheinhessen, was largely spared the direct effects of the war during the Second World War.

The Nazi era is Germany’s darkest chapter. In the commemorative publication for the 1200-year celebration of Harxheim in 1967, this era was not mentioned. The memories of the Nazi era and the Second World War were still too fresh, too many wounds were open or only superficially healed. Some confrontations from the Nazi era continued to burden neighborly relations for decades afterwards.

Until the beginning of the Nazi era, Harxheim had about twenty-five Jewish residents who either perished in concentration camps or were forced to flee under the most difficult circumstances. Questions about the fate of these fellow citizens were hardly ever raised publicly after the war. Only recently has research been done on this topic.

This article attempts, after many decades, to sketch the developments of this time in Harxheim situationally, as far as documentation, photos and contemporary witness reports still allow today.

Harxheim was a typically agricultural Rhine-Hessian community. The entire economic situation was – due to the world economic crisis at the end of the twenties – very tense. Many farms struggled with high levels of debt that left little room for important investments. Revanchism due to the lost First World War, high unemployment and a certain lack of political orientation brought the National Socialist movement of Adolf Hitler a lively influx. The Reichstag elections on March 5, 1933, and the enactment of the Enabling Act on March 24, 1933, were followed by the dissolution and banning of political parties. Hitler had taken power with his NSDAP. The years of unconditional conformity began.

The new Nazi leadership structures were established in every community, including Harxheim, following the same pattern. The politically controlled local group leadership had the say and was in close exchange with the district leadership in Mainz, especially when things had to be settled in the new political sense. There was also a Ortsbauernführer (local farmers’ guide), whose essential task was to document the quantities of seed grain used as well as the harvest quantities brought in to meet the production targets of the Reichsnährstand.

The mayor at the time, Adam Böhm (in office from 1927 to 1946), had to subordinate himself to all this; in the end he was only an executive body. Other organizations such as the DAF (NS-Arbeitervertretung Deutsche Arbeitsfront) had a local chairman in Harxheim. The NS-Frauenschaft(NSF) and the NS-Volkswohlfahrt(NSV) were concerned with matters of “civic common good.” For quite a few citizens, it seemed opportune, for a wide variety of considerations, to join one or another of these organizations quickly. The entire public life was subjected to these structures within a very short time. The population more or less quickly came to terms with the new circumstances.

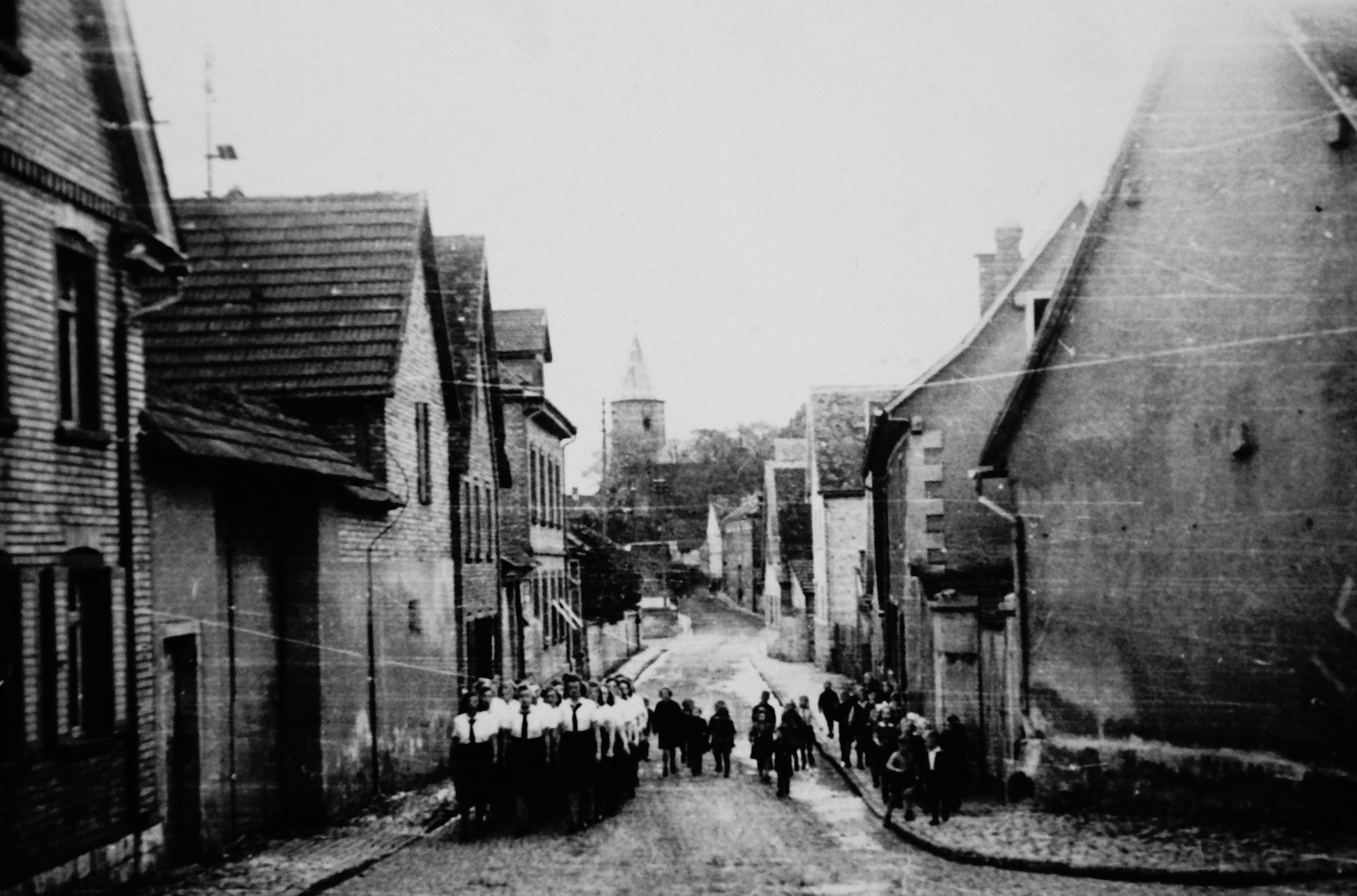

Heinrich Brehm, later mayor of Harxheim, with his future wife Babette on the way to the civil wedding, around 1937

Image source: Unknown

The renaming of the streets was one of the first official acts of the local group leadership in the spring of 1933. As in every town or municipality, the names of Nazi greats of the first hour were quickly found on the street signs in Harxheim: the Obergasse was renamed Horst-Wessel-Strasse, the Untergasse Hermann-Göring-Strasse and the Bahnhofstrasse Adolf-Hitler-Strasse.

The youth fit very well into the National Socialists’ prey scheme and, from a political point of view, could be inspired as a readily malleable target group for Hitler Youth(HJ) and the League of German Girls(BDM). From December 1, 1936, weekly meetings with sports, war games, and chores became mandatory, as did participation in marches and party meetings.

Tense relationship between church and state

The relationship between the church and the Nazi apparatus quickly became strained in the early days. Christian institutions of both denominations as well as their representatives were exposed to spying, hostility and reprisals by the “civil society” unless they showed willingness to make common cause with the “browns”. Church buildings were not spared either. The wooden structure of the Harxheim chapel was completely demolished on Easter Sunday, April 1, 1934, by a nonlocal HJ group.

An exchange of correspondence from 1940 documents how the relationship between church representatives and the local group leadership came to a massive head due to a dispute. Involved in the correspondence was the priest Rachor from Gau-Bischofsheim, who was responsible for the Catholic parish in Harxheim, the Harxheim local group leader as well as the local chairman of the DAF of Harxheim.

The Nazi Women’s Association had installed a cooking kettle in the vacant teacher’s apartment without asking the Catholic parish, which had rented the apartment from the municipality. In this one, the women cooked lattwersch (plum jam) in support of the Winter Relief Fund (WHW). A complaint by the priest, addressed to the head of the local group, about what he saw as the unauthorized use of the rooms for cooking plums was interpreted by the churchman as a sort of “betrayal of the German people or the Wehrmacht,” for whom the plum jam was intended as a homeland greeting.

A rumor that the NSV also wanted to set up a kindergarten in the teacher’s apartment was also unjustifiably attributed to Pastor Rachor. The local chairman of the DAF ended a letter to the pastor with clear threats: “If the pastor and the church council did not apologize or name the person who had started this rumor, the NS district leadership in Mainz would be called in. Everyone knew what this could mean.

War events in Harxheim

From 1942, the intensity of Allied air raids over Rheinhessen increased. Between Harxheim and Mommenheim a searchlight position with anti-aircraft protection and a crew barracks were built. The operating crew consisted of six to eight Air Force soldiers and civilian helpers from Mommenheim and Harxheim for nighttime standby. However, the light anti-aircraft gun did not provide sufficient protection against the U.S. low-flying aircraft that were increasingly attacking Harxheim and our neighboring community of Mommenheim. This position, located in the Auf dem Türkelstein corridor, was cleared in February 1945.

Thecrash of an American B-17 bomber, already heavily damaged by shelling, near the town on August 17, 1943, was probably the most dramatic event of the war. Of the ten crew members, two soldiers were killed, three were reported missing in action, and five became German prisoners of war.

Historical aerial photograph “Harxheim bei Mainz” (16121336: USAAF aerial photograph taken from an overflight altitude of approx. 7,500 – 8,000 meters; scale: approx. 1:10,000; 24.12.1944)

Image source: Aerial photo database Dr. Carls GmbH

Fortunately, the community of Harxheim survived the Allied air raids without any major damage, with the exception of a nighttime firebombing and the associated minor fire damage to a barn (Jerke im Stegklauer estate).

Most of the phosphorus canisters and stick bombs fell in the In der Lieth area or along the southern edge of the village. Furthermore, there was an emergency drop of several explosive bombs outside the village in the direction of Zornheim.

From 1943 until the end of the war, the Harxheim fire department – which at that time was called the fire police – was supported by a women’s fire department under the command of Susanna Bänsch as group leader.

During the heavy bombing raids on Mainz, the Harxheim fire brigade was called upon several times to assist in fire-fighting operations.

Harxheim women with four Polish prisoners of war (center, with (military) caps) in the Wingert, 1942

Image source: Christel Deiß

About fifteen Eastern workers and prisoners of war were employed on the farms of the local community. During the day they did their work in their assigned yards and spent the night in a hall in the Krone house.

Not only food theft but also contact with women were strictly forbidden to the prisoners. In the case of denunciation, this usually meant deportation and the death penalty for the person concerned.

With the beginning of the Russian campaign in 1942, the number of killed and wounded from Harxheim increased significantly with each additional year of the war. Church bells increasingly called for memorial services for a fallen son or husband. The initial euphoria about the war increasingly gave way to the certainty that Germany would lose the war.

On March 20, 1945, about three weeks before the German surrender on May 8, 1945, American troops advanced through Rheinhessen toward the Rhine and Mainz. In the course of this advance Harxheimwas liberated on March 20, 1945 and survived this day without any fighting or casualties.

References:

- Various documents from the archieves of the Catholic parish offices in Gau-Bischofsheim and Lörzweiler, provided by the Catholic parish of Harxheim

- Festschrift for the dedication of the Harxheimer Kapellchen on May 17, 1980, p. 3;

- Festschrift Freiwillige Feuerwehr Harxheim zum 75. Jubiläum am 3-5. Mai 2002, p.18;

- Büllesbach, Rudolf/Hollich, Hiltrud/Trautenhahn, Elke (2013): Bollwerk Mainz – Die Selzstellung in Rheinhessen. Munich. S. 94

- Malerwein, Dr. Gunther (2016). Rheinhessen 1816-2016. Mainz. S. 268-317

- Leiwig, Heinz (2016): Es war ja nichts: Nationalsozialismus in Rheinhessen. Facts, dates, names 1933-1945. Mainz. S. 35-66

- Marschall, Bernhard (2015): Von Mumenheim zu Mommenheim: 1250 Jahre Ortsgeschichte. Mommenheim. S.302

- Contemporary witness reports, own research