The Mainz Basin

Above Harxheim, one has a good view to the south of the beautiful landscape of the Rhine-Hessian tableland and hills. Towards the north, the view falls on the characteristic loess quarry edges at the edge of a plateau. How was this landscape created? And what did it once look like here? Geology answers these questions.

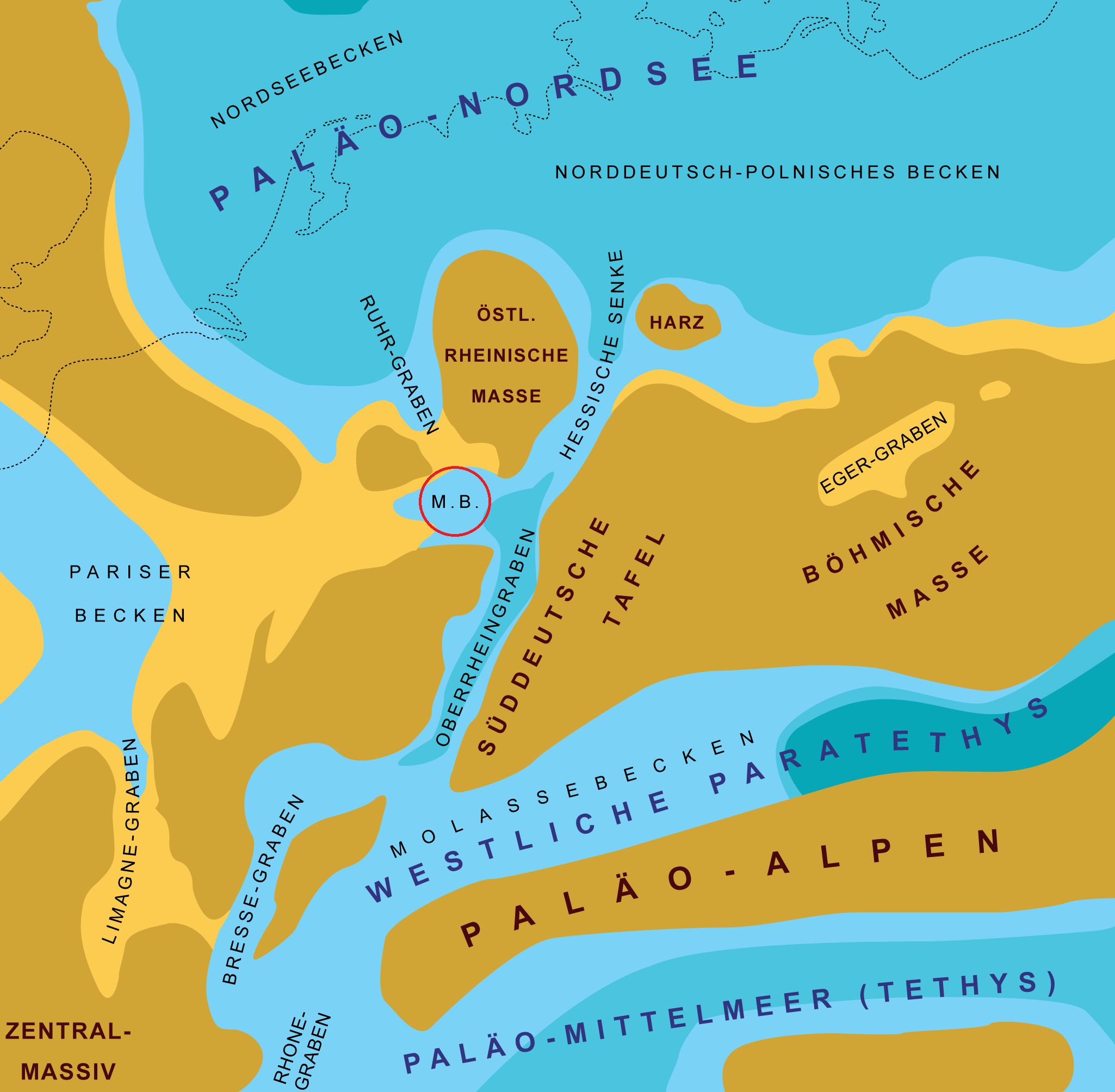

Geologically, Rheinhessen is located in the Mainz Basin, which extends in a triangle between Bingen, Hofheim im Taunus and Bad Dürkheim in the Palatinate. The Mainz Basin is a fossil sedimentary basin and of interest to geologists worldwide. Millions of years old sediments and fossils come to light in many places in Rheinhessen. They provide information about what our region looked like in earlier times and what forms of life there were.

The Mainz Basin was formed in the Tertiary period (66 – 2.6 million years ago). It is the northwestern rift shoulder of the Upper Rhine Graben, which formed about 50 million years ago probably as a result of the folding of the Alps. In contrast to the Upper Rhine Graben, which collapsed by about 3000 m, the Mainz Basin subsided by only about 500 m. The soil of the Mainz Basin consists of the rock unit “Rotliegend”. It was formed in the Permian period just under 300 million years ago. On the Red Slope between Nierstein and Nackenheim, the rock from this period comes to the surface.

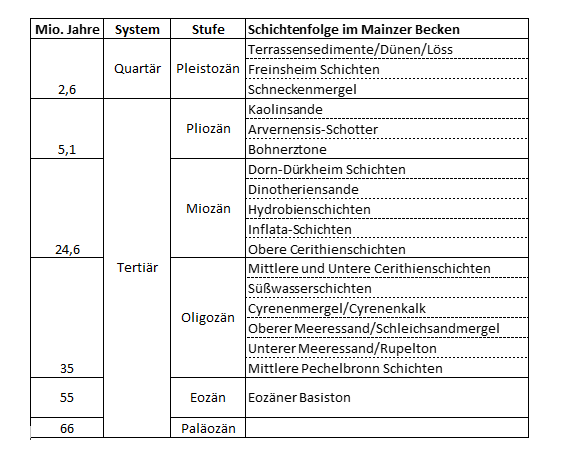

After its formation, the Mainz Basin filled with many different sediment layers under changing climatic conditions over several million years. The individual layers are characterized by typical rock deposits and fossils such as certain species of snails or mussels. It is therefore natural to name the different layers after the rock types or predominant fossils.

For example, the name of the Cyrene marl strata goes back to the ancient name of the brackish water mussel “Cyrena”. Cerithia (pointed cone snails) gave the cerithia layers their name. In part, the naming is also based on the locations where the layer could be detected. Modern research uses still other, but less descriptive outlines.

Sedimentation was particularly pronounced about 31 – 19 million years ago, during which the basin experienced two major flooding cycles. Initially, the sea advanced from the north via an estuary into the Mainz Basin. Somewhat later, a connection with the sea to the south probably also formed via the Upper Rhine Graben. Sands and gravels were deposited on the shores of the created sea bay and sea waves formed the shore rock (sediment layer: lower sea sand). Maritime conditions prevailed, which, thanks to the subtropical climate – comparable to that in Florida – provided ideal living conditions for many creatures. In addition to snails and mussels, sharks, rays and manatees also frolicked in the water, as evidenced by numerous fossil and bone finds in regions near the coast. Particularly rich were the finds in the Weinheim Bay near Alzey, whose former coastal fringe can be hiked.

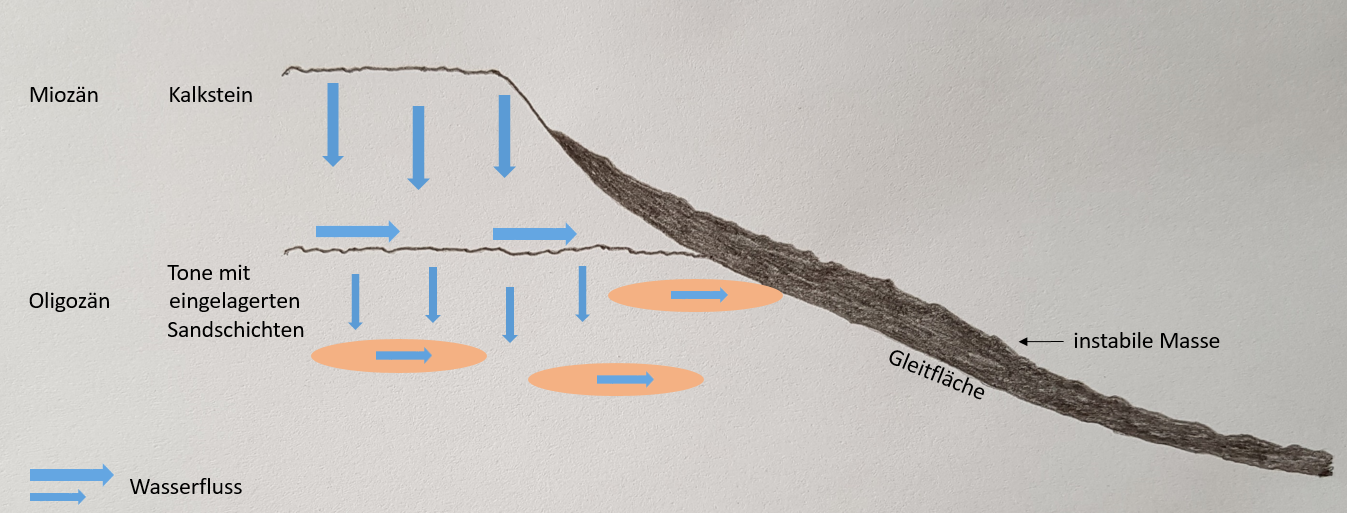

In calmer and deeper marine zones, initially clayey layers (sedimentary layer: Rupelton) and later – under the increasing influence of brackish water (seawater with a reduced salt content) – the so-called creeping sand marls, clay marls with fine sand intercalations, settled (see corresponding layer designation). They still play a major role in Rheinhessen today, as they are responsible for the numerous landslides that occur. During heavy rains, water accumulates in the creeping sand marl layers and flows horizontally, triggering landslides. About 8% or 11,000 hectares in the Mainz Basin area are affected. There are also several designated landslide areas on the slopes above Harxheim.

The creeping sand marls were followed by further marl layers (sedimentary layer: Cyrene marl; marl = calcareous clay). The sea became increasingly brackish and the species richness decreased significantly. Eventually, the marine basin was completely silted up by marine sediments and the subsequent sediments came from deposits in rivers and lakes (sediment layer: freshwater layers).

About 24 million years ago the Mainz Basin was flooded again. During the second flooding, maritime conditions prevailed only for shorter periods. Mostly the sea was shallow and brackish and desiccation crusts developed. Algae reefs formed and land snails were also washed into the water. The sediments from this period are significantly more calcareous than the deposits from the first flooding. The cerithia, inflata and hydrobia layers were formed. Pinhead-sized mudflat snails were the namesakes for the Inflata and Hydrobia layers. About 18 million years ago, the sea finally retreated. The calcareous deposits weathered away. The Mainz Basin became a karstified plateau.

The main sediments that follow are deposits of the Urrhein, which flowed in large arcs from Worms through what is now Rheinhessen in a northwesterly direction to Bingen about 10 million years ago. These are mainly yellowish sands, which occur extensively along the Osthofen – Alzey – Bingen line. Its name Dinotheriensande is derived from Dinotherium giganteum (gigantic beast of terror), an elephant-like animal of which a complete skull was first found near Eppelsheim, south of Alzey, in 1835. Remains of many other mammals such as horses, rhinos, bear dogs, and saber-toothed cats have also been discovered in the sands. You can find out more about life in those days at the Dinotherium Museum in Eppelsheim. There is also a copy of the Dinotherium skull.

In the following millions of years further sediment layers were formed. This also includes the bean clays. These are ore-bearing strata that resulted from weathering processes of limestones and were even mined for smelting in the 19th century. Bohner ores still occur sporadically in the vineyards above Harxheim. Other layers are the Avernensis gravels, deposits of the Ur-Main, and the kaolin sands in southern Rheinhessen near Monzheim, which are also economically important.

Our present landscape was formed relatively late in the period of the Ice Age, which began about 2.6 million years ago. By then, the previously subtropical climate had gradually cooled significantly. The Ice Age period was characterized by a relatively rapid alternation of cold and warm periods. During these changes, incisions were made in the karstified plateau and the plateaus and wide valleys we know today were formed. During the cold periods, thawed soils near the surface slid over the frozen bedrock in slope areas. Moreover, prolonged and heavy rainfall after the end of cold periods probably contributed to the large clearings in the landscape.

Rheinhessen was then part of the mammoth steppe, which was bordered by mighty glaciers in the north and south. Rheinhessen itself was never covered by glaciers. Thus, glaciers played no role in the formation of the landscape.

The loess sediments occurring over large areas in Rheinhessen originate from the period of the cold ages. In Rheinhessen, they were blown in as dust particles from the river gravels during this phase.

References:

Gaby Försterling, Gaby; Radtke, Gudrun (2012): The Tertiary habitat in the Mainz Basin and its fossils. In: Yearbooks of the Nassau Society for Natural History. Volume SB 2. pp. 19 – 32.

Kuhn, Winfried (undated). Geology of the Mainz Basin. Script for Culture and Wine Ambassador Rheinhessen.

State Office for Geology and Mining in Rhineland-Palatinate. Safe building in Rhinehesse. 2nd ed. Version 2014-12-04

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mainzer_Becken

* Gretarsson,%C3%,%C3%CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>;, via Wikimedia Commons, red circle added.